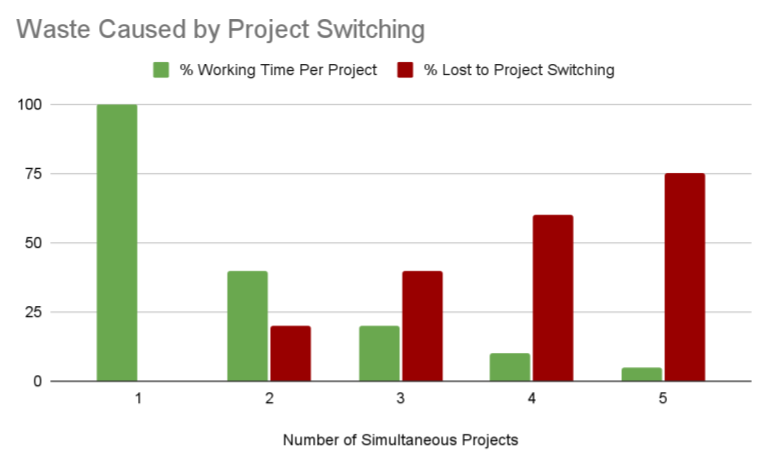

Agile Fundamentals: Waste Caused by Context Switching

Gerald Weinberg’s book “Quality Software Management: Systems Thinking” is nearly 30 years old. While it’s not one of the most highly-read and recommended Agile classics, its the source of a frequently quoted table of data:

(Source: Weinberg, Gerald M. (1992) Quality Software Management: Systems Thinking. Dorset House, p. 284.)

Visualized as a graph, the waste caused by context switching really stands out:

Worse, the waste caused by project switching isn’t due only to the losses related to cognitive overhead. Failure to prioritize often leads to less revenue and even building the wrong product.

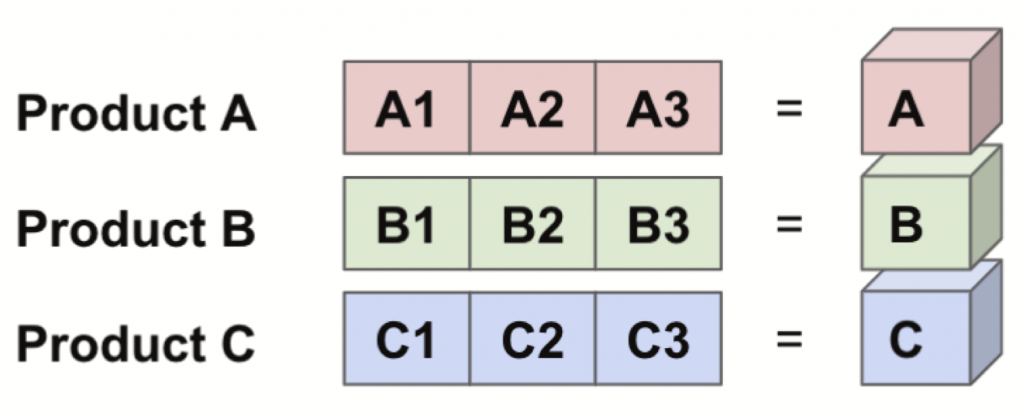

(Credit where credit is due: I first saw a version of the following illustrations from Jeff Sutherland, who adapted it from Henrik Kniberg. I’ve expanded on them a bit.)

Let’s suppose your company wishes to ship three products: A, B, and C. To ship a product, a development team must complete tasks 1, 2, and 3 corresponding to that product:

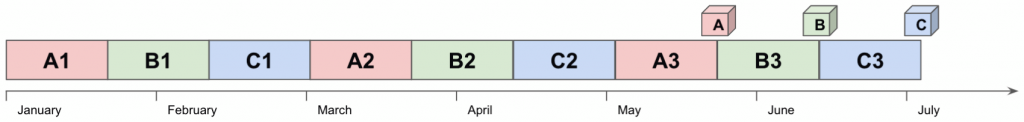

Most companies are not very good at prioritizing work. As a consequence, the prevailing belief is: “Everything is important. Get started on everything immediately!” The traditional delivery timeline might look like this:

Notice that we are interleaving each task and that products A, B, and C are ready at roughly the same time, several months after we started.

You could also represent the traditional approach on a roadmap, like this:

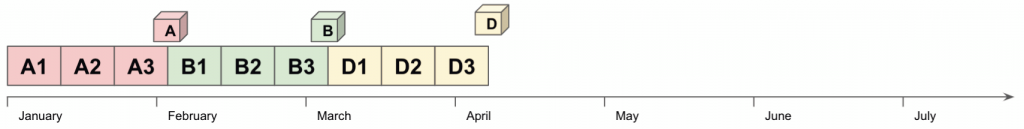

The Agile approach is very different. Instead, we proactively prioritize the work and focus on limiting our work in process:

There are at least three significant advantages to this Agile approach.

First, we lose 20% or more of our productivity in the traditional approach due to context switching waste. In this example, the company could go about twice as quickly if they switched to developing one product at a time instead of three.

Second, it gets worse, though! Because we have nearly finished products B and C before finishing A, we had to do nearly three times the work (not including the context-switching waste) before we could ship Product A (in late May). Had we prioritized and focused, we would have been able to ship Product A in early February. Had we done so, we may have been able to collect revenue and feedback from our customers starting nearly four months earlier. In fact, the savings from not context-switching between projects may mean that we could ship products A, B, and C before we would have been able to ship just A in the traditional model.

Third: products are rarely independent, and building the wrong product can be costly. In this example, we believed before starting the work that the customer needed Product C. We took the Agile approach and built A (more valuable and/or cheaper) first. When we delivered A to our customers in early February, we learned that they liked it a lot and didn’t need C after all. Instead, they wanted us to work on D. We took February to finish most of B and get the initial prototypes for D built.

So, we can see that prioritization and focus serve everyone: developers, stakeholders, and customers. Further, good prioritization is often not a zero-sum game. Many stakeholders will argue aggressively for their product to be worked on right away (and it’s no surprise: they may even have a bonus tied to it being completed by a certain date). However, the waste caused by project switching and the cost of delay is so significant that failure to prioritize may make all stakeholders worse off. In this case, the stakeholders behind projects A, B, and C agreed to prioritize based on the cost of delay and all were better off than if they had insisted that everyone’s work be tackled at once.

What’s next? How to prioritize the work, coming soon.